FSP FAS 140-3: Plugging a Hole in GAAP — Or Another Off-Balance Sheet Financing Gimmick?

I subscribe to a listserv for professors of accounting (http://pacioli.loyola.edu/aecm/) to discuss emerging technologies, pedagogy, and pretty much anything else. One of the recent topics of discussion on the listserv had to do with the impact of accounting complexity on preparing students to become auditors. One participant in the conversation offered up the following quotation from a masters student’s paper on the bogus reinsurance transactions between AIG and General Re:

"When companies are involved in these complicated transactions, auditors often don’t have the time, training, or knowledge to spot questionable items. When I audited a financial services company during my internship, I didn’t really understand their business let alone the documentation that I was reviewing to ensure that controls were operating properly. So much of the work we conducted was based on mimicking the prior year’s work papers that even after levels of review I believe fraud could have easily slipped by." [italics supplied]

Coincidentally, FASB Staff Position (FSP) FAS140-3, Accounting for Transfers of Financial Assets and Repurchase Financing Transactions, has been recently finalized; this student’s lament came to my mind while I was attempting to decipher the new accounting rule.

In order to begin to explain the FSP, you need to know that FAS 140, Accounting for Transfers and Servicing of Financial Assets and Extinguishment of Liabilities, contains criteria that restrict "sale accounting" on transferred financial assets when there is a concurrent purchase agreement. Consequently, “repurchase agreements” (repos) may be subject to "loan accounting" instead of sale accounting. The difference in accounting treatments is as follows: under sale accounting, the asset comes off the balance sheet and is replaced by the proceeds from sale; under loan accounting, the asset stays on the balance sheet, so the credit offset to recognition of the proceeds is to debt. So most significantly, sale accounting is off-balance sheeting financing, and loan accounting is on-balance sheet financing.

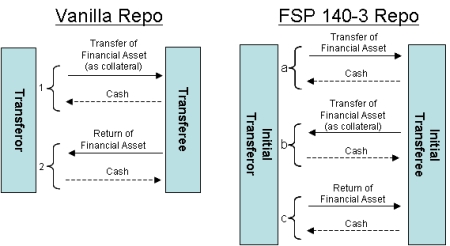

To the financial engineer attempting to defeat the best efforts of investors and/or regulators of financial institutions, loan accounting is a bad thing, and sale accounting is good. So, one important challenge for them is how to fabricate an ‘arrangement’ that gets under FAS 140’s fence to permit sale accounting. This appears to have been invented by a mortgage REIT through a variation on the repo (essentially a round trip for the asset) whereby the financial instrument now makes one more trip back to the original transferee. If you’re confused, this picture may help:

The vanilla repo is essentially a collateralized loan, with the legal title to the collateral held by the lender during the term of the loan. Since the asset makes three trips under the FSP FAS140-3 version, the argument is being made that the initial transfer is not part of a repo–and that the second and third trips constitutes a repo in reverse. The accounting argument is that if the initial transfer appears to be economically de-linked from the subsequent two transfers, then the accounting should be de-linked as well. The FSP is needed because FAS 140 does not directly address this point, and it provides that the first transaction could be eligible for sale accounting–if the criteria in FAS 140 for sale accounting is also met.

Thus, the FSP provides "guidance" (i.e., the hoops the lawyers and financial engineers have to jump through) for determining whether an initial transfer of a financial asset and a "repurchase financing" (the last two transfers) can be de-linked. The first hoop is the most important, and the one that will cause accountants, both young and old, to have acid reflux: does the arrangement have a valid business purpose?

A valid business purpose? Ha! Prior to SEC rules restricting revenue recognition for bill and hold sales, did these arrangements have a valid business purpose? Maybe one percent of them. The other 99 percent were mere schemes concocted to end-run pesky revenue recognition criteria. I can’t vouch for this, but my strong suspicion is that the arrangement subject to FSP 140-3 springs from the same primeval instincts as the bill and hold sale. In other words, the presumption of a "valid business purpose" would be a fiction 99 percent of the time. No matter what the bells and whistles of the arrangement are (if you can understand them from reading the contracts), the motivation is the accounting result.

Never mind the judgment exercised by the FASB in publishing what amounts to a user’s manual for yet another off-balance sheet scheme, one must ask whether the FASB is tone deaf or indifferent to the recently inflamed ire of investors and politicians with off-balance sheet accounting. And, while financial services are the targeted beneficiary of FASB largess, you never know when some Fastow-type CFO is going to apply it by "analogy" to their own nefarious machinations involving power plants, energy contracts, leases or what have you.

So, good luck dear accounting students; here’s hoping your first assignment is not to audit a financial services company, or some other innocent looking dog that bites like the big, bad wolf.